The Colonel sent me an interesting article today about Mark Ross. It's an interview conducted by The Hollywood Reporter shortly before Mark's death.

You can read the article here. Loads of pictures, too.

A longtime character actor, Aesop Aquarian was the Zelig of L.A.'s free-love counterculture, roaming from the Manson Family ranch to the commune of Father Yod. At the end of his life, he finally decided to tell his story: "I'm going, 'Wait a minute, they want me to kill these people?'"

BY GARY BAUM

JULY 15, 2022

When Aesop Aquarian returned from acting class to discover an acquaintance dead of a gunshot wound in his spare room, he let it go.

Perhaps it had been a game of Russian roulette, or a suicide. At least these were the theories offered to him by his new Venice Beach housemates, members of what the public would in time call the Manson Family.

Later, when Aesop’s beloved custom Volkswagen camper van was mysteriously torched after he resettled with the group on their compound 30 miles north at the Spahn Movie Ranch, he accepted it. Maybe it was just an accident. Mercury could well have been in retrograde.

But Aesop finally bugged out, hitchhiking back to Los Angeles before dawn, after it was proposed he turn assassin in the run-up to Charlie Manson’s trial. “There was no humor in the suggestion,” explained Aesop, who then still went by his birth name, Mark Ross. “It was matter-of-fact, like going down to the store to pick up some sugar and flour. ‘Oh, and by the way, kill [prosecutor Vincent] Bugliosi and the judge.’ ”

This is just one of Aesop’s true fables. He died May 27 at 77 years old, after speaking at length about his life with The Hollywood Reporter.

In the entertainment industry, he was a bit player, not a leading man, making ends meet with background work, music gigs and assorted side hustles. Where he starred, though, was in his own epic journey across the vivid margins of the entertainment industry, from Old Hollywood to New Hollywood to the Streaming Beyond. He’s a window into a vanishing world. Think Forrest Gump, but sharp-witted; Barry Lyndon, but downwardly mobile; Cliff Booth, but a hippie. Think fiction, but it happened.

***

Aesop grew up wealthy in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles, when the name of the local Country Mart still reflected the largely bucolic setting’s avocado groves. The wife of neighbor Cecil Kellaway, an actor twice nominated for an Oscar, “used to give us marmalade because she used the oranges from our trees.” He took Kellaway’s career advice to heart: A star has “five years, maybe 10 years if you’re lucky. But as a character actor, you could work forever.” Other neighbors included Cesar Romero, Fred MacMurray, and Judy Garland and her husband, Vincente Minnelli.

Weekends were spent goofing off at the Beverly Hills Hotel’s Sand and Pool Club, where his family had a membership. He remembered catching sight of Lauren Bacall when he was of a tender age. Marvin Davis, still decades away from his acquisition of 20th Century Fox as well as the resort itself, would often make a move on the family’s favored cabana.

Aesop’s maternal grandfather, Albert Kahn, was a Jewish Lithuanian immigrant turned New York merchandising tycoon and philanthropist who came to own, among other businesses, Spear & Co., the country’s largest home furnishings chain as of the early 1950s. Aesop’s father, a West Coast executive for the family’s rubber-manufacturing business, was his son’s nemesis.

“[Aesop] was outwardly rebellious, and he got into shit-tons of trouble — smoking cigarettes, running away — and he was beaten by Dad,” says Don Ross, his younger brother by six years, now a licensed marriage and family therapist. “We didn’t come from a typical Jewish family in that we weren’t very close. We had two emotionally immature parents. Dad was extremely self-involved, narcissistic. Mom wanted to be kind of a celebrity wife — she wanted to be in that role. She was very prone to uncontrolled rages and screaming. She was betting her whole future on this love she hoped she’d get from my dad, and that didn’t happen. It was like trying to get blood out of a stone.” He adds: “The core issue in our family was that there just wasn’t much love.”

Aesop was sent to a boarding school catering to the kids of the rich and famous in Idyllwild, three hours east of Los Angeles. “Back then we were called ‘problem children,’ ” Aesop explained. “Today, we call them ‘creative.’ ” He roomed with Frank Sinatra Jr. The two formed a band called the Outhouse Four. They played ballads and folk songs: Aesop on string bass, Sinatra on piano and serving as emcee.

Aesop, who’d been interested in acting since he played with puppets as a child, studied performance at what’s now the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in Canada. Landing the role of Theseus in a school production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream set him on a lifelong path. “I was terrible — jiminy Christmas, was I bad,” he said. “But I had the part, and it did spoil me forever. Getting your own dressing room, your own makeup girl: The bug bit me. There was no question about what I wanted to do for a living from that moment on.”

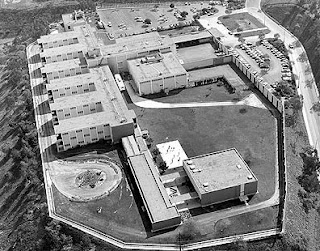

But first, Aesop volunteered for the Marine Corps, encouraged by President Kennedy’s admonition to “ask what you can do for your country” as well as the indebtedness of a Jew not far removed from America’s fight against the Nazis. (“I have relatives that died in the oven.”) However, the inveterate misfit, a self-proclaimed “trickster,” never shipped out to Vietnam, instead turning his three years of active-duty service into, by his account, a blend of Catch-22 and Three’s Company by taking advantage of the military’s commuted rations policy, which permitted soldiers to receive an allowance in lieu of meals if they resided off-site. So, while Aesop officially was based out of California’s El Toro air station in Orange County, the military helped support him while he lived with his girlfriend and her UCLA roommates in a Westwood apartment. “What a great time to be a healthy young man,” he recalled. “It was after the pill and before AIDS and before herpes.”

That girlfriend, who now goes by Carol Davidson Baird, fell for him in November 1965 when she heard him playing folk music along the Sunset Strip at The Fifth Estate, a hub for the city’s emerging political New Left. “He had the most beautiful bass voice and jet-black hair,” she says. Later, he won over her parents by singing the kiddush, a Jewish ceremonial prayer, over dinner: “My father had a glow, like I’d finally found a nice Jewish boy. But it was a roller-coaster-ride relationship.”

The couple were soon engaged. Yet the relationship foundered when, after leaving the military, he abandoned his plan to pursue a degree in psychology so that he could seek work as an actor. “He was unemployed and didn’t have a pot to piss in,” Baird remembers. Still, for a time, the “stormy romance” flared — as when, in 1969, after a motorcycle accident that left him in a cast up to his waist, she arrived to comfort him and they put on the unreleased music of a local underground artist. “We were listening to Charlie Manson on reel-to-reel.”

***

On an autumn day in 1969, Aesop encountered a couple of young women panhandling in Santa Monica. “I told them I didn’t have any change, but I had a house in Venice, and I had an open-door policy,” he said. “Anybody who could handle the scene inside was welcome to stay.”

About the scene he’d established at 28 Clubhouse Ave.: “Number one, we didn’t wear any clothes. Number two, no one locked the bathroom door — the door was off its hinges.” Third, “if you couldn’t deal with making love in front of other people, then you could go to the ‘shy’ room. But when you’re loving and you’re caring, you don’t mind making love in front of other people that are loving and caring. It’s no big deal.”

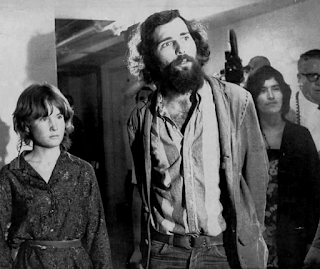

It turned out that the women, Susan Phyllis Bartell and Madeline Joan Cottage, were part of a commune that called itself the Family, and soon they and a handful of their companions, male and female, were living at Aesop’s pad. While their group was already on the radar of both law enforcement and the media — police had recently arrested key followers as well as their leader, Charles Manson, on auto theft charges — the Family had yet to become shorthand for countercultural darkness. The notorious Tate-LaBianca murders, which claimed the lives of seven people including actress Sharon Tate and hairstylist-to-the-stars Jay Sebring, had occurred the previous summer, but the culprits had not yet been apprehended.

Aesop thought he’d found his tribe. Having grown his hair long — and, he believed, been hounded constantly by the local cops because of it — he figured the new circle amounted to fellow unjustly hassled hippies. They were on his wavelength, after all, sharing his sexual adventurousness, social rebelliousness, fondness for acid and openness to New Age theoretics. Most also had troubled relationships with their parents. “There was a lot of Scientology game going on,” he explained, referring to the new housemates’ interest in the self-improvement doctrines of L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics. “It was a 24-hour-a-day therapy session. They’d call you on your bullshit.”

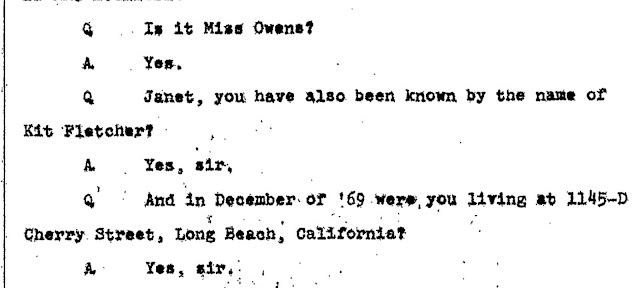

Things went sideways Nov. 5, 1969, when Aesop returned home from acting class to find police in his home and learned that a Family associate named John Philip Haught, also known as Zero, had died in the shy room. The death would be ruled a suicide, but questions have persisted about the responsibility of Family members who were there when it happened. Cottage, who went by Little Patty and was in bed with Haught when he died, reportedly claimed he shot himself with a .22-caliber revolver — owned by Aesop — in a larkish moment of Russian roulette. (Among other troubling revelations, the gun reportedly was found wiped clean of fingerprints.)

Bruce Davis, a Family member convicted of two killings tied to the cult — of aspiring musician Gary Hinman and stuntman Donald “Shorty” Shea, who worked at Spahn Ranch — was another Aesop housemate at the time of Zero’s death. He’s also long drawn suspicion among observers who wonder whether the Family believed Haught had become a problem in need of solving. “There are a million possibilities,” said Aesop, who was “freaked out” to later learn of Davis’ involvement in the Hinman slaying, which occurred a little more than a week before the Tate-LaBianca killings. Like him, Hinman played music and did drugs — and had an open-door policy for the Family at his own place in Topanga Canyon.

In a letter to THR from San Quentin State Prison, where he continues to serve his sentence after Gov. Gavin Newsom blocked a 2021 parole recommendation, Davis described Aesop as “a generous host,” reminiscing that “he had a good 12-string guitar.” As for Zero, Davis cited Little Patty’s statement and the official police report ruling the death a suicide. “So sad,” he wrote, in summation. (Aesop said of Davis and Manson: “They were both ex-cons that grew a beard. They weren’t hippies.”)

After Zero’s death, Aesop became closer to the group. “I was completely open with them,” he recalled, “except at night, when I closed my eyes, I’d sort of go, ‘Well, I wonder if I’m going to wake up tomorrow.’ ” Still, he remained with the Family and moved to Spahn Ranch. “I didn’t just live there; I worked it,” he said. “Get up before the sun, eat a big breakfast, take the horses out.”

He got to know Manson only during prison visits, which were encouraged by Family members. (While held on the auto theft charges, Manson was indicted for murder and conspiracy in the Tate-LaBianca killings.) “Charlie and I got along well from the second we saw each other, we really did,” he said. “I understood him as a being. Not as Charlie Manson, drug-crazed being. Just as a spiritual being, living in the body of Charles Manson.” Noting that as an actor, Aesop believed he was especially attuned to performative behavior in others, he made clear: “I think Charlie played crazy really well.”

Of Manson and his most famous followers, who were also indicted for the Tate-LaBianca killings, “I felt they were innocent until proven guilty. I also know that it’s not unusual to be arrested for something you didn’t do. It happened to me a couple times.”

Aesop, who chauffeured the remaining female Manson followers from the ranch to the courthouse each day in his van so they could support their leader from the spectators’ gallery, believed that Manson, regardless of his culpability, received an unfair trial. “Just a very sad circus,” he said, highlighting the judge’s decisions not to allow Manson to represent himself (“They threw me in jail [for contempt of court, for five days] because I made a comment to the judge about that”) and, later, not to call a mistrial after President Nixon declared to reporters that the defendant was guilty, which prompted national headlines.

Still, “I knew that living on the ranch was not the safest place in the world for me to be.” This bad moon rising became glaringly apparent to him one night when his van — one-of-a-kind, with double doors on both sides; he called it The Great White Whale — “was completely and totally gutted” by fire. Nobody on the ranch provided a suitable explanation. “It broke my heart. It really did.”

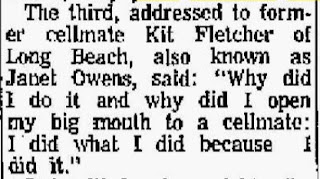

Then, when it was floated that Aesop assassinate Bugliosi and the judge — “I can’t honestly remember if it was Squeaky [Fromme] or Brenda [McCann] or Sandy [Good]” who first brought it up — he left the commune. “All the scales from my eyes fell,” he said. “I’m going, ‘Wait a minute. They want me to kill these people?’ That was the end-all, be-all. Goodbye, yeah. I didn’t last a day past that.”

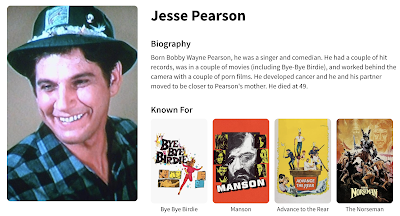

Yet before Aesop severed ties with the Family, he claims he proposed the idea for, and brokered the necessary participation required to complete, a film about the group that became Manson, which was nominated for a best documentary feature Oscar in 1973. In retrospect, he declared, his uncredited assistance in gestating “my baby,” as he refers to the project, is a fact that “I’m proud of, and a little aggravated about,” since it didn’t turn out as he’d hoped.

The co-directors, Robert Hendrickson and Laurence Merrick — respectively, a fellow student at his acting school and the teacher of their class — have both since died. “Everything was sensationalized,” Aesop said. “The whole idea of making a movie was to give these people humanity, and it gave them none. It was 180 degrees from what I had in mind.”

The film infamously opens with a gun-wielding female Manson follower asserting in a chilling, possessed tone: “Whatever is necessary to do, you do it. When somebody needs to be killed, there’s no wrong, you do it, and you move on.” Aesop believes that, like their leader, the women in the film “were trying to act like they were crazy” to gin up lurid mystique, scare the squares and play along with filmmakers they’d decided were dupable, predatory or both. “[The women] weren’t anywhere near that way with me,” he said.

***

Aesop soon established half a world’s distance between himself and the Family. “I was living the life of a one-legged, blind sadhu” — a Hindu sage who’s renounced earthly attachments — “in the holy city of Varanasi” in India. “I would bathe in the Ganges every morning.” He eventually ended up passively suicidal in Afghanistan, taking Mandrax, a qualuude-like sedative. “I woke up with my wrists and my ankles tied to a hospital bed in a Kabul prison.” He doesn’t recall much about how he ended up there, except that when local police had engaged him, “my Marine Corps training came in, and I guess I fought.”

His psychologist brother, Don, who didn’t speak with Aesop for the final six years of his life, in part over the distribution of their parents’ estate, contends that Aesop long fostered “this kind of impenetrable persona of acting like he’s just the coolest and most controlled and most self-possessed guy in the room. It’s just bullshit.”

Aesop, then still Mark Ross, found himself again in music while pushing farther east to Asia, and decided to forgo his surname. “I’m not attached to my name; it’s not who I am,” he said. “I became Mark Elliott. My attitude back then was ‘Why not?’ It still is. I’m pretty much open to most things.”

He began gigging clubs in Laos and Thailand, later crooning “Everybody’s Talkin’ ” — the folk-rock tune popularized by Harry Nilsson in 1969’s Midnight Cowboy — across the Hong Kong airwaves. “I’m probably the first country western singer on Asian television,” he mused.

In time, Aesop made it back to L.A. By 1972, he’d formed a street-performance duo, the Singer and the Silent Partner, alongside a pantomimist. That mime, Sheldon Rosner, recalls that the partnership lasted seven months. “Aesop, who was calling himself that because some of the songs were fables, was a real control freak,” he says. “He’d play guitar and sing songs and I’d act them out according to the story. His idea was to do it exactly the same way every time — no variance. I was like, ‘I need a little freedom to improvise, to be myself.’ He didn’t like that.”

Before the pair broke up, Aesop encountered the charismatic, controversial leader of another L.A. commune known for its female followers. Father Yod, of the yoga- and meditation-focused Source Family, handed Aesop a $100 bill while he and Rosner performed in the plaza at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Soon, Aesop joined their fold, which included attractive acolytes in flowing robes, a mansion in the Hollywood Hills and a pioneering vegetarian restaurant along the Sunset Strip, called The Source, which was frequented by the likes of Warren Beatty, John Lennon and Julie Christie. (It’s where Alvy Singer orders his “plate of mashed yeast” in Annie Hall.)

Half a century on, Aesop wasn’t interested in dwelling on similarities between Manson and Father Yod, or why he’d been drawn to the realms each had conjured. “It’s sort of more than my brain can deal with,” he said. He did acknowledge that he and Father Yod “had a lot of things in common,” ticking off everything from being Marine veterans and their recent voyages through India to mutual interests in leather-working and Eastern religion. Also: “He liked living with a lot of girls. I liked living with a lot of girls.” (Aesop claimed to have “been with over 2,000 women,” and acknowledged he “was a little devious” in that “I did not use protection because I wanted to have a lot of children.” Father’s Day, he asserted, was “the unhappiest day,” since he figured he had plenty of kids he’d never met.)

Rosner, who now works as an astrologer, says he, too, was captivated by the group’s spiritualism, but quickly pulled away. “What I saw was that it was indeed a cult,” he says. “There was a harem around Father, who really took sexual advantage around a lot of these young girls, and I think Mark was in it for a piece of ass.”

Aesop, who like other members of the Source group took the surname Aquarian (“out of respect, the same way that Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali”), was candid with the new faction about his then-recent history among Manson’s crowd. “The thing about Charles Manson, that was the time when everyone was in a crash pad or finding a commune, and some of our people could’ve gone to their group or they could’ve gone into our group,” explains Isis Aquarian, who helped run The Source as an administrator and produced a 2012 documentary about it, The Source Family. “The teachings of spirit are the same, but they could be used for white or black. Charlie Manson used them for black magic.” She says Aesop “made choices [in his life] that weren’t all good,” but that she believes he was “an innocent.”

Still, Manson proved to be the undoing of Aesop’s Source era. Father Yod, who fancied himself a matchmaker, knew that one of his female disciples also had, as Isis Aquarian terms it, “some previous energy” with Manson, and pushed for the two to pair up. Aesop wouldn’t go along with it — even if this meant displeasing his metaphysical master. “I’m sorry, I’m a bachelor then, I’m a bachelor now,” he said. “And I’m not going to hook up with somebody because they’d be a good match. That wasn’t going to play.”

Besides, as with the Marines and Manson’s group, it was in his character to remain apart. “I’m not much of a joiner,” he said. “How do you explain it? You’re in it, but not of it; you’re of it, but not in it.”

Aesop kept gigging all the while, honing his country-hewing folk act to that of, as he put it, a “sit-down comedian.” In August 1976, he qualified for his SAG card, earned $232 and outmaneuvered the celebrity judges on NBC’s The Gong Show with a performance of his self-composed ditty “The Shortest Cowboy Song,” in which he sang a laconic lyric (“It’s been lonesome on the saddle since my horse died”), strummed his guitar with a flourish of finality, then walked offstage before the panelists even had the chance to gong him. “They have to give you at least 30 seconds,” he recalled.

Odd jobs kept him afloat over the years, from managing apartment buildings to sales work. But he identified most as a jeweler, designing his own pieces. He was known to don bracelets up to his elbows on each arm, with three rings on every finger and a load of necklaces. Then he’d visit industry hangouts — Ciro’s, Dan Tana’s, Musso & Frank — and take a seat at the bar to hawk them, ordering his signature drink, a Grand Marnier and coffee with a twist of lemon peel. He’d prop a business card in the brim of his cowboy hat that read: “The jewelry store is open.”

Aesop also found customers on set, selling custom pendants shaped like coke spoons (“passed around like party favors back then”). Barbra Streisand purchased a sterling silver necklace featuring black and red coral when he had a small role as a recording engineer in her 1976 version of A Star Is Born. “Everybody complains about Barbra, but she was nothing but a sweetheart to me,” he said. “I figure people that have bad things to say about her, they’re carrying around their own grief.”

Aesop’s acting career peaked in 1977, when he played Simon Marcus, a Manson-esque cult leader on Starsky and Hutch. He believes he landed the role — auditioning in front of Starsky himself, Paul Michael Glaser, who was directing the episode, titled “Bloodbath” — because he opted for the understated. “If I played it low-key, it would be even scarier,” Aesop said, recounting his thinking at the time. Of Glaser, he recalled, “He shuddered. He went, ‘Scared the hell out of me.’ ” Nobody involved with the show knew Aesop had been associated with the Manson Family.

He thought his biggest break, and steadiest paycheck, might be in the offing when he secured the part of a sea captain in a short-lived 1990 live-action Disney Channel program, Little Mermaid’s Island, featuring puppets from The Jim Henson Company. Then Henson died, and so did the show. “Oops,” he said.

As Aesop doggedly auditioned, he joined a clique of men who hung around Hollywood’s Gower Gulch, on Sunset Boulevard east of Vine Street, shooting the shit as they pursued their creative dreams. They were latter-day counterparts to the working cowboys who decades earlier had corralled themselves at the same spot (which by this point had become a strip mall), in search of jobs in the then-dominant genre of Westerns. “They all had cool stories,” says Sue Kolinsky, a veteran nonfiction producer (Top Chef), who for a time shot footage for a documentary about Aesop and his friends. “One guy managed music acts and had found the Beach Boys, actually named them, but couldn’t hold on to them; another had been John Cassavetes’ stand-in. Aesop was getting parts in music videos,” including for Ziggy Marley and Kanye West.

As his dark beard grew longer, scragglier and grayer, he joked that the background roles he secured had certified him for “the 3-H Club: hippies, Hasidics and the homeless.” He played a warlock on Power Rangers, a buccaneer in Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End, a rabbi in You Don’t Mess With the Zohan, a village elder for Iron Man 3, a vagrant on I’m Dying Up Here and an old pioneer in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

Aesop could tap into personal experience for the homeless roles. “I let him stay [overnight] in my office for a couple of weeks,” says Victor Kruglov, his longtime manager. “Nobody knew about it. This was in the 2000s. He was a very nice guy; I never gave up on him.”

Cordula Ohman, a friend of Aesop’s since the 1960s, recalls him at one point living out of a storage area in Hollywood. “I thought he hadn’t kept himself together, to be living like that,” she says. “He was stubborn and driven — he wanted to do his art. He wasn’t willing to give up. He’d go through any lengths, even if he had to sleep in the street.”

Aesop had since improved his situation, renting a modest courtyard apartment in Hollywood, north of the Paramount lot. In May 2021, he experienced a freak accident (cigarette, oxygen tank) that resulted in a burn down his throat and the transformation of his admired bass voice into a pubescent rasp. He became a recluse.

It was during this confinement that Aesop spoke to THR, his health wavering and then descending through his final year. Rumors had swirled around him since the ’70s. Yet he’d chosen to disclose little, if anything, about his past — even to his confidants. Now, at the close of what he knew to be his final act, he’d decided to take a curtain call.

Hours before Aesop died, he sent THR an email: “Please call there are 2 or 3 things you must hear from me before you publish … PLEASE!” Attempts to respond went unanswered. It’s unknown whether these were to be revelations or renunciations — or mere clarifications.

Essra Mohawk, who had a romance with Aesop in the 1970s that turned into a lasting friendship, says the committed bachelor, aware he was near his end, had recently asked her to marry him. “He wanted me to have the monthly wife-of-veteran payments,” she explains. “I should’ve believed him when he said he was dying. If I did, you’d be talking to Mrs. Aquarian.” A singer-songwriter and protégé of Frank Zappa, she intends to sing at Aesop’s memorial service, planned for September at the Frolic Room, the Hollywood dive where everyone knew his name.

“He was a very complicated character,” says Don, his estranged brother. “It’s telling that he was a Pisces, whose symbol is two fish swimming in opposite directions, but bound together. You get extremes with Pisces — it relates to Jesus but also to those in the theater.” He adds: “Aesop was always looking for a sense of significance in the world.”

Many of Aesop’s belongings, as well as his 15-year-old Tibetan spaniel, Lady, have been brought to the Hollywood high-rise apartment of his close friends, Maya Sloan and Thomas Warming, a writing-team couple who became his caretakers during his last year and are embarking on a book about him. “He’s a true Hollywood creation,” says Sloan, “an outsider even among outsiders.” One who, as Warming puts it, “weaves in and out, like a cameraman, who happens to be in the wrong places at the right time.”

Aesop Aquarian’s own Age of Aquarius fulfilled its promise of long hair and free love, if not, necessarily, harmony or enlightenment. Before he died, he said he had found resonance in a Kurt Vonnegut line from Cat’s Cradle: “Peculiar travel suggestions are dancing lessons from God.” It was, he explained, “the way I live my life.”

This story first appeared in the July 15 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.